THERE has been a big disagreement within Welsh Labour, writes LlanellI MS Lee Waters.

There has not been a ‘witch-hunt’ against Vaughan Gething, but there has been a genuine conflict of values.

Now, there is an appetite to move on quickly, but I think there’s a real danger that in shutting down discussion, we will neither understand nor learn the lessons of what has happened.

As uncomfortable as it will be, I think we need a proper debate about Welsh Labour’s future direction. Circling the wagons around a ‘unity candidate’ may bring some short-term relief, but it will do nothing to address the fundamental need to renew in office.

I have not given any interviews and don’t intend to, but to make sense of it all, I’ve written this assessment, which examines what should happen now and analyzes how we got to this position.

These are offered in the spirit of honest debate and not point-scoring.

Edrych ymlaen

We’re in a pickle. After 25 years as the largest party in the Senedd and 102 years as the party of Wales, we have become the establishment.

Our opposition is weak, and so, like many political systems where single parties dominate, we turn on ourselves from time to time to check power and keep ourselves honest.

We are currently in the midst of the biggest schism since 1999 when the ‘pluralist’ section of the party embodied by Rhodri Morgan went ten rounds with the ‘machine politics’ section of the party represented by Alun Michael and beat ten bells out of each other. Those bruises took a decade to heal.

The last four months have seen the same happen again, albeit beneath the surface. The inevitable resignation of Vaughan Gething has brought that into the open, and now party leaders are desperately trying to keep a lid on it by brokering a quiet deal to avoid any further open conflict.

How do we ‘heal the wounds’? This question has frequently bleeped across my WhatsApp over the last week. The instinctive response is to come behind a ‘unity candidate’, and all will be well. I completely understand the instinct and necessity of pulling together in a common cause.

Disunity is a genie that is very difficult to get back into the bottle. However, unity is not an end in itself; if that becomes our primary focus, it risks a search for the lowest common denominator.

Unity is a consequence of renewing in office. It is the end result of the process of reaching an agreement. It follows an exchange of ideas and is not some precondition for a contest where the less that is said, the better.

There are honest differences, as there should be in any group of intelligent adults, let alone a political party. We need to talk them through and test the arguments. Persuade and then decide.

We are not a management committee; we are a political movement. We were created for a purpose—to bring about change for working families, challenge power, make society fairer, and be a voice for the voiceless. That requires passion, hunger, and courage to reshape and reform ourselves as a political force to meet the modern context and do the same for our society.

I think the new MP for Swansea West, Torsten Bell, hit the nail on the head, “The question”, he said, “is whether social democrats can turn themselves from simple defenders of the system into insurgents”.

That’s the real challenge to the people who wish to lead.

In a brilliant speech to a Labour Party conference in Manchester some years ago, Bill Clinton told delegates that unless they presented themselves as the agents of change, somebody else would fill the gap. “Make no mistake about it,” he said, the question for voters “is not whether you will change. It’s how you will change and in what direction.”

The central question of this leadership contest should be how we can meet the appetite for change while honouring our values as a political movement.

If we can’t answer that question, then this may well be our Scottish moment.

After the collapse of the Labour Party in Scotland, Jonathan Powell, the PM’s Chief of Staff throughout the whole Blair period in office, said that Scottish Labour had become a hollow tree—all it took was someone to come along and push it for it to fall. Nobody wants to hear this at the moment, but this could well apply to Welsh Labour, too.

There’s nothing inevitable about any of this. The difference between us and Scottish Labour in 2011 is that we have a long record of devolved governments to be proud of and a proven ability to stand up for Wales.

But the voters aren’t daft, and the warning signs are clear enough for those who want to look for them in the General Election result. Whereas the Westminster voting system this time flattered us, the new, more proportional voting system we’ll be using in Wales will be far less forgiving if our support levels don’t get back beyond the 30% threshold. The last YouGov poll put us at 27% at a Senedd election – just 4 points ahead of Plaid.

The voting system we’ve legislated for will actively work against us if our numbers stay at that level and a generation in the wilderness awaits.

As I write, that’s where we’re heading, and people are panicking. So, the ‘we must unite’ banner is quickly pulled up the flagpole, and the call has gone out to rally around. My worry is that superficial unity is, in fact, counterproductive. To avoid having to go there, we have to be prepared to do the hard work of remaking our unity based on a real consensus of approach, not a backroom deal.

I have been boringly consistent on this point. Ahead of Rhodri Morgan’s resignation, I urged the party to challenge ourselves to focus on a programme of reform and talk about ideas.

When Carwyn Jones stood down, I again urged colleagues not to flock to candidates until they’d heard what change they would advance (there’s a clip of me saying just that that’s survived!). “Labour does not have a divine right to rule,” I said at the time; “We have to show people we have a vision for change”.

When Mark Drakeford announced his retirement, I gave a substantial lecture to the Brecon & Radnor CLP outlining my views on some policy challenges and urging those who wished to succeed him to remember that “We’re not managers; we’re agents of change.”

I can’t say I’ve had much success in persuading people, but I’ll try again.

Yes, there is an open wound. But it will not heal itself; it has to be stitched. We need a genuine debate about ideas and policies and an outcome that gives a mandate for a way ahead. If we duck that incredibly difficult challenge, then we will have missed perhaps the last opportunity to win the next Senedd elections.

Edrych yn ôl

So how did we get to this point?

I’ve been writing this assessment to try to make sense of a remarkable seven months in Welsh politics. Rather than give anonymous briefings or radio interviews, I’ll set out my reflections openly and honestly as a contribution to the record and to the process of figuring out what we do next.

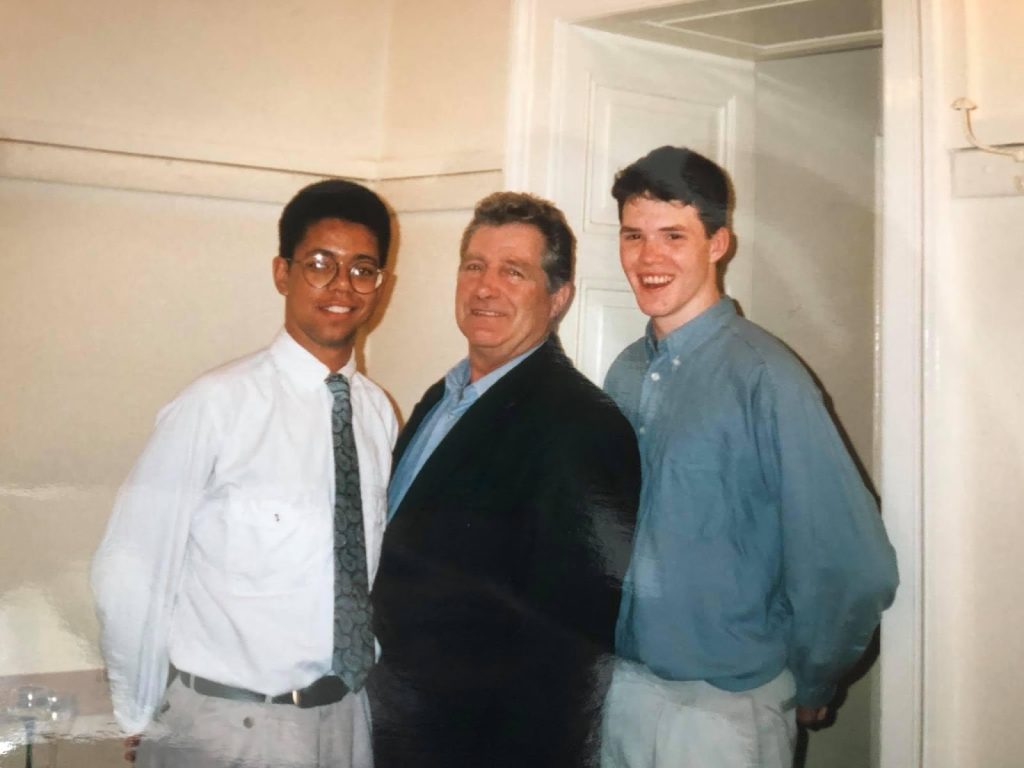

It’s been thirty years since I joined the Labour Party. I can clearly remember the moment I first met Vaughan Gething in 1994 at Aberystwyth University Students Union. He worked the room with effortless ease, a warm and natural smile, a charm and a chuckle. And he hasn’t changed.

March 1996, Vaughan Gething, Joe Wilson MEP, Lee Waters

I worked alongside him in Government during the awful covid period and thought he was admirable. In particular, I was deeply impressed by the calm, professional and sober manner in which he absorbed enormous pressure and contributed to the grown-up way the Welsh Government handled an unprecedented crisis.

Mark Drakeford was spot on to say in his assessment that:

‘Vaughan is a much, much better person than he has been portrayed in certain newspaper outlets and in some of the commentary around him. I have worked right alongside him over that decade. He is a thoughtful, committed, hardworking individual who tries to do his best. Now, there’s a big difference I think between trying to criticize somebody for their judgement. We all make mistakes, and we all answerable for the judgments we make; and accusations that somehow this person was not fit to be First Minister’.

I didn’t support him in either leadership contest because of honest political differences of substance (Vaughan supported Alun Michael in 1999, and I’ve firmly moved to the Rhodri / Drakeford view). But I’ve always liked him and got on with him, and I am genuinely sad that his time as First Minister came to an end in the way it did (and I did try to offer advice that would have avoided this).

My criticism of Vaughan as soon as the very large donations to his campaign became known has been around his judgement in trying to work around the party spending rules to outspend his opponent colossally and, as a result, rely on donations from a range of sources that were at best problematic (Interestingly even in private not one of the people who I’ve spoken to who supported him have even attempted to defend the decision to take the money).

He has never acknowledged that he was wrong to do either of those things. His failure to confront this ‘original sin’ (as I called it in our group away day) and his lack of humility each time he was challenged began to be seen by people as hubris. It fundamentally weakened his position and caused his authority to ebb away.

“The trail that eventually led to last week did begin right back there with that original decision, the fuse was lit. And Vaughan was never able to escape it,” Mark Drakeford reflected two days after the resignation in a typically sage contribution.

My principal reflection of the way things have developed over the last few months is one of bewilderment that people can look at the same set of facts and reach such different conclusions.

In announcing his resignation to the Senedd, he said, “A growing assertion that some kind of wrongdoing has taken place has been pernicious, politically motivated and patently untrue.” He told the Senedd on the afternoon of his decision to go after four Ministers resigned from his Cabinet. In 11 years as a minister, I have never, ever made a decision for personal gain,” he said.

In his fair-minded assessment, Mark Drakord reflected:

‘I think it can fairly be laid at Vaughan’s door that at mistakes were made. Now he would defend them and he would explain why he made the decisions he made, but the criticism that mistakes are made, I think, is a legitimate one. It’s when that shades into accusations that these weren’t just mistakes, but these were somehow dishonest mistakes, or mistakes that were done to somebody’s lack of integrity in office, that I think is completely unfair.

To be completely clear I don’t for a second suggest any improper motivation for his conduct; but while he was learning Law at Aberystwyth University I was across the campus studying politics, and the first thing I remember being taught was that perception is more important than reality.

Set aside the much-publicised stench of the extraordinary donation from David Neal, I think the equally problematic donation from taxi firm Veezu has attracted no attention. Bear in mind at the time of the leadership election, we were in the process of passing a taxi reform Bill which has now been ditched. Vaughan took a £25,000 donation – which is the single largest donation to a Labour leadership campaign (before the Dawson one) – from a company at loggerheads with trade unions, who until recently was also paying right-wing Conservative Alun Cairns.

We now had the extraordinary spectacle of a First Minister announcing on the floor of the Senedd that we are failing for the second time to honour a manifesto commitment to bring forward legislation on taxi reform (instead, we are to have a draft Bill, which is something) and being forced to add when making the announcement: “Members may wish to note a declaration of interest concerning the company Veezu”.

Never before has a First Minister had to declare a formal conflict of interest on a key matter of Government business.

The fact it has passed without a single comment tells us something about where we have reached.

When I spoke out in the Senedd about the donations, I rooted my objections in the damage this was being done to political culture and democratic norms. Here’s what I said:

The point about devolution, this place, a Parliament we have created from scratch, is that we set higher standards. Twenty-five years ago, we talked of devolution as the beginning of a new politics, but the reputation of politics and politicians seems to be lower than ever.

The First Minister told a Senedd committee last week that the controversy has not affected his approval ratings. I must say that it surprised and troubled me. Whether the polls bear that out or not, it really isn’t the point. Surely, the question isn’t what any of us can get away with; it’s what is right.

The fact that some voters just shrug their shoulders is what should worry us. Far from being an endorsement, I fear it’s a reflection that we are all tarred with the same brush. And we all get it – you’re all the same; you’re in it for yourselves; you’re on the make. Not only is it really demoralising for many of us who see politics as a genuine public service, a sacrifice, but it’s also dangerous to the fabric of our democracy at a time when it’s already under huge strain.

Academics call it ‘norm spoiling’.

They say that when accepted standards of behaviour and norms are undermined, expectations are lowered, and a new set of weaker standards can take hold. That is why we need to confront this situation.

I have felt increasingly dislocated by the fact that so many people in the Labour Party have been prepared to turn a blind-eye to what the public has been able to see very clearly. But ultimately our political culture has asserted itself and acted.

The rules for the Welsh Labour leadership contest were that candidates could spend up to £45,000 on their campaigns. Vaughan raised £251,600.

This party spending cap excluded staffing, office and travel costs. The rules assumed that volunteers would primarily run campaigns and that ‘staffing’ would not be a significant factor.

I can only assume that having lost one leadership election he was determined to do all that he could to win this one, which would probably be his last shot at the leadership. He recruited a paid staff team, including the deputy political editor of the Daily Mirror, Ben Glaze, as Deputy Head of Communications. Labour members were bombarded with text messages and letters within days of the contest starting. This was a well-organised and funded campaign. And there’s nothing in principle wrong with that. Vaughan is quite correct in saying that he did not break any rules. But rules can’t cover every eventuality.

I remain firmly of the view that in deliberately sidestepping the spirit of the spending rules, he made a significant error of judgment. He didn’t need to spend so much and shouldn’t have. This resulted in him seeking and accepting money from people whose agendas clash with ours and are perceived to be seeking to buy influence.

It seems that Vaughan remains unwilling or unable to confront his own role, though. Several colleagues told him after the election that he should return the donation, but he chose not to.

“If he’d said sorry about the donations, if he’d acted differently, would we be in this situation right now” ITV Wales presenter Rob Osborne asked my colleague Hefin David in the immediate aftermath of the resignation. “Yes, I think we would. This was predestined”, he replied.

I couldn’t disagree more.

Perhaps Mark Drakeford’s response to this was the most definitive, though. He told the BBC WalesCast pod:

‘My own observation with a bit of a distance was that there was a great deal of goodwill available to him in the earliest days. I think people were absolutely proud to have the first black leader anywhere in Europe here in Wales…People who hadn’t supported Vaughan joined his cabinet and were willing to take up important positions and to be part of the government’

Vaughan Gething has said he tried to do the right thing ‘for other people and for the country’ to keep Welsh Labour united, but people were not willing to accept his election as leader. He said:

“Members across the movement in Wales had a one member, one ballot contest, which I succeeded… There was an opportunity for all of us to get behind that result, as has happened after every other leadership contest. That hasn’t been possible”.

So why wasn’t it possible? Vaughan doesn’t seem to consider his own role in this.

The election result was very close. Vaughan won 51.7% of the vote. Jeremy Miles took 48.3%. The Labour Party has refused to publish the actual number of votes he won, but Jeremy’s campaign manager told the Walescast pod that the result was ‘within a few hundred votes’.

As well as the enormous disparity in funding, the closeness of the result threw attention onto the pivotal role played by the regional committees of trade unions which overwhelmingly supported Vaughan Gething – with some very sharp practice in evidence.

In addition to this, the fact that Jeremy had the support of a clear majority of Welsh Labour Senedd members, council leaders, and Constituency Labour Parties intensified the closeness of the result.

A win’s a win, and it would clearly have been claimed had the situation been reversed. However, academics point out that in order to create legitimacy, election winners need to establish what they call ‘losers’ consent. Here is an example of a situation where the winner needed to work hard to build legitimacy and win over the consent of the losing side.

In the first meeting of the Labour Senedd Group after the result, it was clear that there was disquiet. The closeness of the result, the donations, the influence of machine politics and the fact that the majority of Labour MSs supported a different candidate all created conditions that called for a deft and humble approach.

Vaughan conceded a review of funding rules for future elections and appointed his rival and his key allies into important posts, but that’s as far as it went.

Mark Drakeford again:

Here’s the approach that I took to trying to lead a group of 30 people. It’s a very small group that has varying views – all political groups have a range of views. I thought I needed to do two things. First of all, I need you to pay the closest attention not to the people who I knew were likely to be supporters of the things I was going to do, but the people who would have the biggest reservations or doubts, that’s where I needed to focus my attention.

I needed to make sure that those people who might have doubts, that I spent as much time as I could talking to them, making sure that they knew that they were being listened to and that they were included in the decisions that were being made in some ways.

You have to take for granted that people are going to support you because they’re going to support you, but you need all those 30 votes. You need every single one of them including the person who is furthest away from where you might be on that spectrum. And those are the people you’ve got to think about, the people you’ve got to invest your own time and effort.

And then secondly, I tried to encourage a culture in which we tried to see the best in one another. And we tried to give each other the benefit of the doubt. Because in a group of 30 people, you know, somebody’s going to say something that won’t be exactly what you would have said, or somebody will have an opinion that you rather wish they hadn’t chosen to in front of other people. But what you want to do in a small group of people is to give that person the benefit of the doubt. They’re not going to be doing it for harmful reasons. And if you have a culture where people are prepared to do that and think the best of one another rather than the worst of one another, then I think you’ve got a bit of a recipe for keeping that difficult show on the road. And if you’re not careful, sometimes, when things are very difficult, things tip the other way.

Vaughan did not demonstrate that level of skill in party management.

Instead, he seems to become increasingly resentful and exasperated by the fact that the story of the donations is not going away and that people are not giving him the benefit of the doubt. He feels he is being held to a higher standard than others.

There are a number of people who sincerely hold the view that Vaughan has been subject to a vindictive and persistent character assassination campaign driven by unconscious racial bias.

I’ve tried my best to understand that viewpoint and was particularly troubled by the statement issued by the Welsh Labour BAME Committee, which said they felt the treatment of Vaughan had “crossed a line between fair examination and racially influenced attitudes and judgements, with a Black person being held to a higher standard”. Their statement challenged members of the Labour movement not to be bystanders and to stand “firmly behind Vaughan” against this subconscious racial prejudice; “we are seeing this play out before us, and we must act to stop it” their statement added.

I am someone who considers myself anti-racist, and as Transport Minister, wrote the instructed Transport for Wales to co-produce an anti-racist plan as part of their funding conditions. However, clearly, I am not black, represent an area with very low levels of BAME people, and have only a small number of friends who are people of colour, so I am very aware of my potential for unconscious bias.

I met with a member of the group to try to understand the pain behind the statement better. We had a very friendly and constructive conversation. My summing up of our hour-long conversation, which they didn’t challenge, was that quite clearly, as a black Welshman, Vaughan had experienced racism all his life, and the bar he was being asked to meet was higher than for others. To his supporters in the BAME community, in particular, his election as First Minister was a profound moment of hope and validation, and they wanted his colleagues to get behind him. And they shared his frustration that people seemed unwilling to move on, in a way that they may have done had he been white.

As the committee statement concluded,

“There have been many moments of reflection over the last few years in which people and institutions have accepted how subconscious racial prejudice can creep into the things they do and say . We believe we are seeing this play out before us, and we must act to stop it. That is why we are speaking out, standing firmly behind Vaughan Gething, and calling on all in our movement to be allies not bystanders”.

People will make their own minds up about this. I am very conscious about my limits in being able to make a fair judgement, but I don’t deny that this is what some felt deeply. But it is perhaps fair to say that if this analysis is correct, and Vaughan was being held to a higher standard, then that is all the more reason not to take such outsized donations from controversial sources, which would give rise to damaging criticism. If you are a trailblazer, that is all the more reason to make sure you are above reproach. And that’s on Vaughan alone.

From my point of view, the situation could have been salvaged at several points if he had been willing to confront his error of judgment. But at every stage, he compounded it and even sought to deflect blame onto others.

I’ve never thought Vaughan Gething was dishonest or dishonourable. But he showed terrible judgement, which, the longer he refused to concede, undermined him in people’s minds. In the YouGov poll published two days before the General Election, voters were asked how well they thought he was doing. 0% sent ‘very well’, and only 12% said fairly well.

It is clear that Vaughan very sincerely does not believe that he did anything wrong, and that was the fundamental problem for me.

One of the reasons the last three months have been so painful in the Welsh Labour Party is that the schism that has surfaced has revealed a genuine tension in values. I literally felt sick when I felt compelled to speak out against what I saw as ‘norm spoiling’ behaviour, and when my cry of pain was ignored, I made myself ill with the thought of endorsing this amorality in a confidence vote. I couldn’t do it, and I didn’t do it.

I drafted a private note to Vaughan, which, in the end, I didn’t send as he hadn’t responded to any of my messages, but it summed up how I felt:

I know you think you are being held to a higher standard than others. I honestly don’t – unless you are comparing donations at a UK level that we have rightly condemned.

It is a terrible argument to make and one contradicted by your decision to advise the UK party that they should not keep the underspend. If it was a problem for them to use it, why wasn’t it a problem for you?

The argument that you won’t be involved in any decisions is disingenuous and beside the point. It reinforces the view that we are slippery, venal and insincere.

The polls now clearly show that this has cut through, and people feel you should not have taken the donation and, having taken it, should give it back.

The way you have dealt with the situation has revealed further character traits that clash with the values I expect from a leader

“Everyone has to look at themselves and what they’ve done,” Vaughan Gething said in his first interview after he announced he couldn’t continue. Sadly, he was directing this at others.

We now have to try and come together and heal. But let’s learn the lessons of these two torrid months – the best way to resolve disagreements is to address them openly and honestly. People don’t like divided parties, but they like dishonest ones even less.

This article appears on Lee Waters’ blog here